The sun had barely risen over the mist-covered hills of Ratnapura when the first pickaxe struck stone. The sound echoed through the valley, a familiar rhythm to the men who’ve spent their lives digging for treasure beneath the earth. This is Sri Lanka’s gemstone country, where the ground yields sapphires as blue as the Indian Ocean—if you’re willing to risk everything to find them.

The miners of Ratnapura work in conditions that haven’t changed much in centuries. Armed with little more than shovels, buckets, and an almost mystical knowledge of the land, they descend into hand-dug pits that can plunge 30 meters below the surface. The walls are unstable, the air is thick with humidity, and the threat of collapse is constant. Yet every morning, they return. For many, it’s the only way to feed their families. For a lucky few, it’s a path to unimaginable wealth.

Local legend says the gods scattered blue sapphires across Sri Lanka as a gift to the island’s people. The reality is far less poetic. Most miners will never hold a stone worth more than a few dollars. They work in cooperatives, splitting whatever meager profits their finds generate. A typical day might yield nothing but blisters and exhaustion. But then—sometimes—the earth gives up something extraordinary.

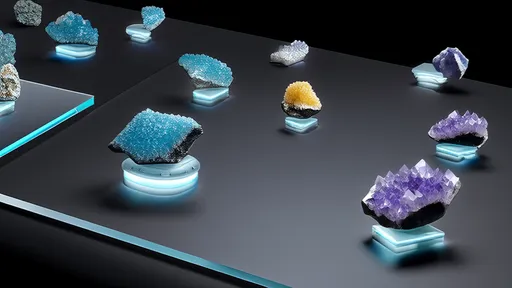

Last season, a team uncovered a 1,400-carat cornflower blue sapphire cluster in a pit no wider than a man’s shoulders. The stone, later named "The Pride of Ratnapura," sold at auction for enough money to rebuild every hut in the village. Such discoveries are rare, but they fuel the dreams that keep the mines operating. Every miner carries a story about a friend of a friend who struck it rich, reinforcing the belief that tomorrow could be the day fortune smiles upon them.

The sorting process is where expertise separates pebbles from prizes. Women and children typically handle this work, their trained eyes scanning buckets of gravel for the faintest glimmer. A true Ratnapura sapphire isn’t just blue—it’s said to contain "liquid light," a velvety depth of color that seems to shift under sunlight. The best stones go to brokers who’ve maintained family connections with European jewelers for generations. The rest end up in tourist shops or are sold by weight to cutting factories in Bangkok.

Monsoon season brings a different kind of danger. Floodwaters can turn pits into death traps within minutes. Last year, three brothers drowned when their tunnel system collapsed during heavy rains. The community mourned, then returned to work once the ground dried. There are no safety inspectors here, no government oversight—just the unspoken rule that every man watches his neighbor’s back when descending into the earth.

Modern mining corporations have tried to mechanize the process, bringing in heavy equipment and geological surveys. But the locals resist. They believe the land rewards those who approach it with respect, not bulldozers. There’s truth to this: The most valuable stones still come from ancestral plots worked by hand. Industrial mines often crush delicate crystal formations, while the artisanal miners extract them intact.

As evening falls, the men gather around oil lamps to share stories and examine the day’s finds. A young boy proudly displays a pebble with a faint blue streak—his first sapphire. The older miners humor him, knowing this small success might determine whether he spends his life in the pits or escapes to the city. For now, the mines continue to whisper their promises, and the people of Ratnapura keep listening.

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025

By /Aug 19, 2025